Arm-Z: an extremely modular hyper-redundant low-cost manipulator — development of control methods and efficiency analysis

Introduction

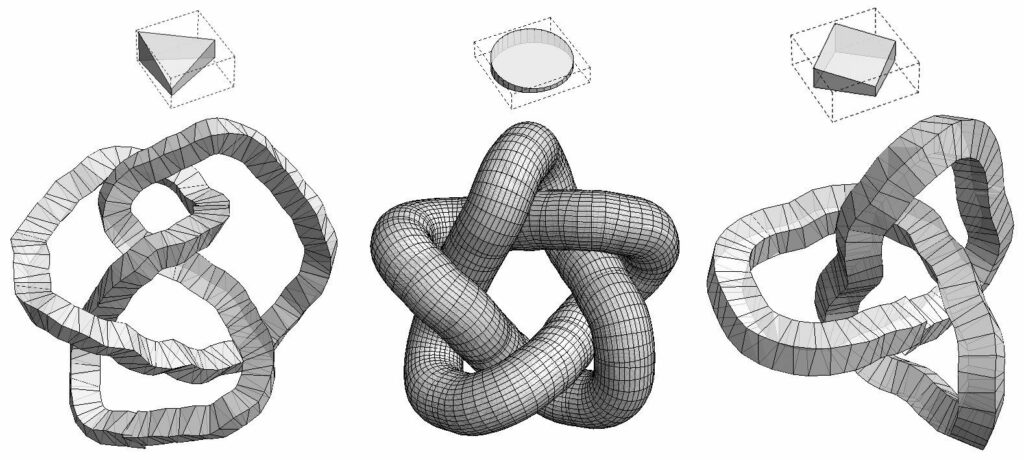

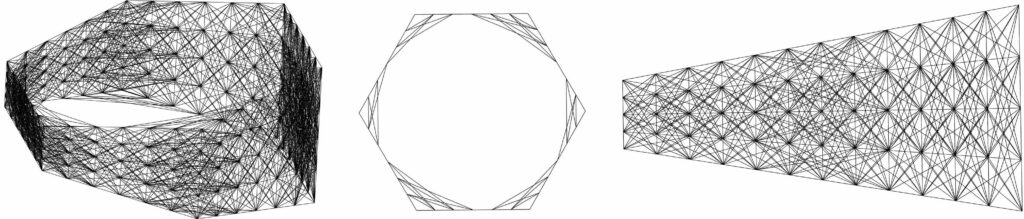

Extremely Modular System (EMS for short) is a novel approach to the design of architectural and engineering forms and structures introduced by the applicant a few years ago. It is a family of concepts where assembly of congruent units allow for creation of free-form shapes [1]. Fig.1 shows examples of mathematical knots constructed with one type of module. EMSs are multidisciplinary and gradually gain attention in various fields of research: architecture, civil and space engineering, structural mechanics and computer science.

The two major advantages of all EMSs are: economization (due to mass-production), and robustness (the modules which failed can be easily replaced, also if some fail, the system may still perform some desired tasks). However, the disadvantage is that their assembly and control are non-intuitive, and rather difficult. In other words, combining non-trivial congruent units to form meaningful structures or their kinematic actions are computationally expensive. Nevertheless, due to availability of modern computational power, proposed here approach is rational and competitive.

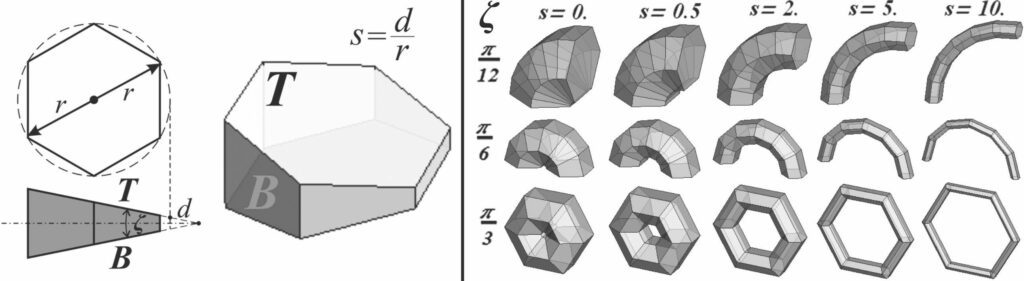

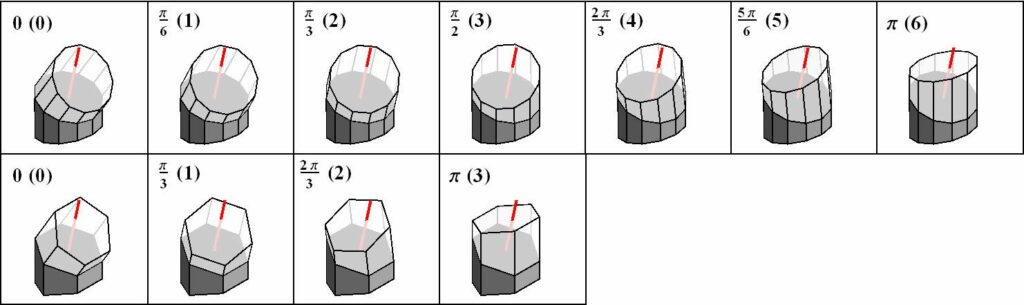

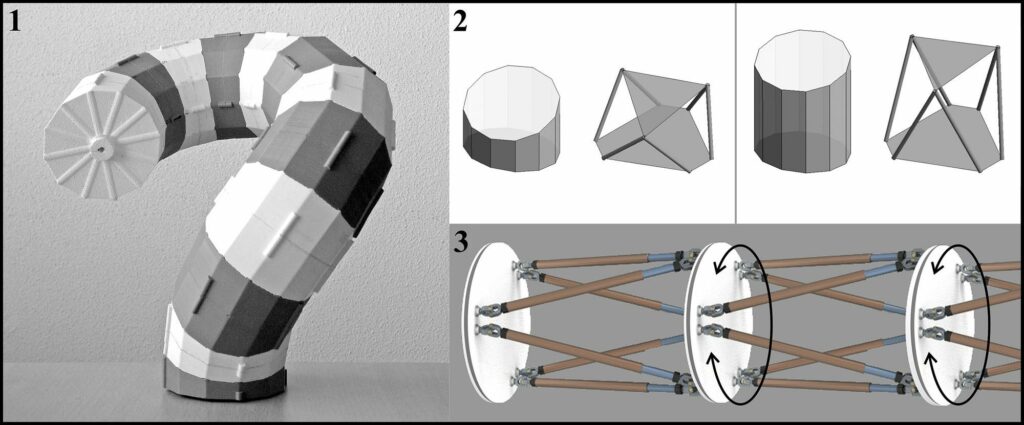

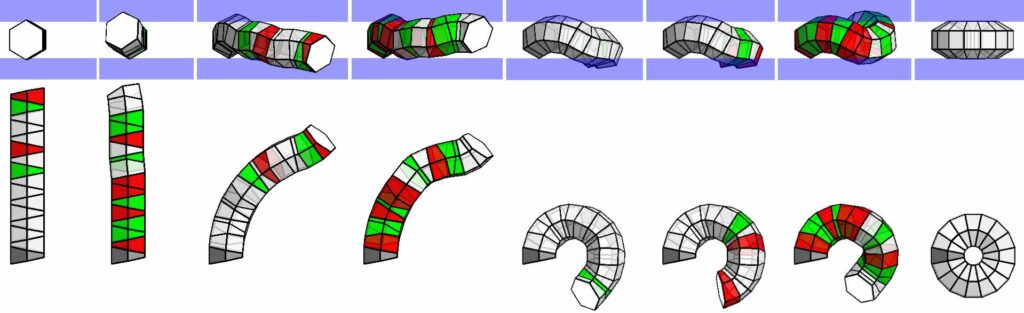

Arm-Z is a conceptual manipulator composed of congruent modules each having one degree of freedom (1-DOF) – a relative twist introduced by the applicant in 2014 [2]. Simple changes of these twists result in emerging behavior of the entire Arm-Z allowing it to perform complex movements. The relative twists can be continuous or discrete. Arm-Z modules are geometrical objects analog to a sector of circular torus. Each module is defined by parameters: number of sides k, size r, offset d, and angle ζ between bottom (B) and top (T) surfaces. Fig.2 illustrates these parameters.

On the right: examples of simple assembly of modules with various combinations of their geometrical parameters.

The motivation behind creation of Arm-Z:

- Pipe is simple and relatively easy to make structural element, particularly efficient in omnidirectional bending. This is the case where a structural system is to be universal, in other words when the bending direction is unknown beforehand.

- Earthworm is a class of inspiring pipe-like and segmented (quasi-modular) species which shows exceptional adaptation to extreme environment.

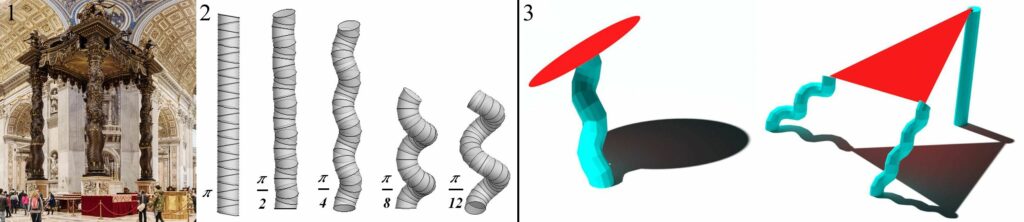

- By nature, pipe-like structures are hollow, which enables auxiliary internal functions such as habitation, communication, transportation, sprinkler/flotation systems etc., as shown in Fig.3.

- Modularity is a rational way of economization of construction. It allows for mass-production of congruent elements which can therefore be relatively sophisticated but still inexpensive. Modularity also enhances the system robustness, as the malfunctioning or worn-down units can be replaced by compatible ones.

- Responsiveness, adaptation, reconfigurability, deployability and dynamic control are major challenges in modern engineering addressing problems in always-changing environment. Moderns structures must not only be structurally sound, but should also intelligently respond to the changes of both environment and the users’ requirements.

Scalability of the concept

The concept of Arm-Z can serve in challenges of various scales:

- Habitats and emergency structures for extreme environments both on: Earth, in outer space, under sea, etc. Analogous system has been recently proposed as a deployable construction system e.g.: for space habitats and emergency connectors [3], as shown in Figs.3.1 & 2.

- Oil containment booms (Fig.3). Such a system could be quickly deployed from an aircraft and could be globally controlled or self-organized based on the local neighborhood, i.e. water state (clean/contaminated) and/or state of adjacent modules.

- Architectural elements such as Solomonic (helical) columns of controllable arc length, curvature and torsion (Fig.4.2 & 3). Such elements could be re-configurable and even responsive (kinetic).

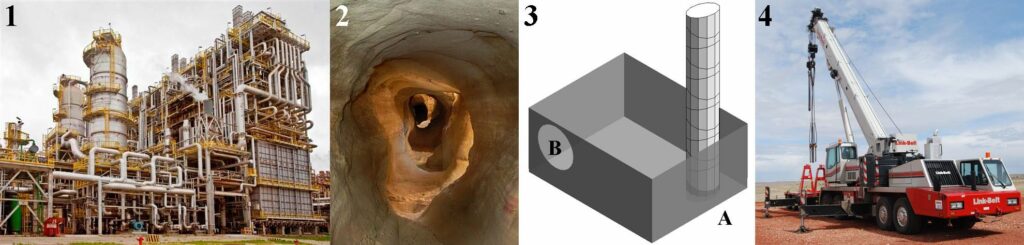

- Adaptive minimally-invasive industrial „endoscopes” for inspection of narrow channels, pipes and gaps for renovation and servicing. Such adaptive hyper-redundant mechanism could be used for maintenance of industrial facilities, where topology and geometry of objects and installations are known, e.g. in petrochemical pipe systems which have to be inspected from the inside (Fig.5.1).

- A tunnel boring machine (TBM) excavates tunnels with a circular cross section. It is an expensive, but much safer alternative to drilling and blasting (D\&B) methods. The proposed system could be used for securing such circular or irregular tunnels; in particular for microtunneling (e.g. for emergency oxygen supply in a rock burst, seismic collapse etc.) with ability of „meandering” around particularly hard objects/layers or obstacles (Fig.5.2).

- Robotic hyper-redundant manipulator e.g. for cable or flexible pipe installations, especially in hazardous 3D environment with obstacles (Fig.5.3).

- Free-form adjustable stabilizers for heavy vehicles, especially for uneven ground (Fig.5.4).

- Most importantly, the number of modules in Arm-Z can be changed, so its length can be adjusted to optimally suit the given task, as e.g.:

- a portable inspection/manipulator device e.g. for security or military applications;

- a manipulator for confined spaces, where its length is crucial for safe operation;

- a (micro) tunneling system with a boring head, extending along with the bored tunnel.

The potential economic benefits

The potential economic benefits of the proposed system result from mass production of the Arm-Z modules. It is expected that they will be relatively sophisticated, however, such exceptional modularization allows for extreme optimization of the production process of each identical unit. This project focuses on basic research and the physical demonstrator, after critical evaluation will shed more light on this issue. It will be possible to make meaningful assumptions on the economic feasibility of the Arm-Z concept and EMSs in general.

Scientific goal of the project

The overall shape of Arm-Z is a result of: the geometrical parameters of each module, number of modules and their relative rotation. Fig.6 shows Two Arm-Z modules of different bases at consecutive dihedral twists from 0 to π. The numbers in parentheses indicate the consecutive positions. The first (bottom) module is fixed and indicated in gray. The axis of rotation for the subsequent module is shown in red.

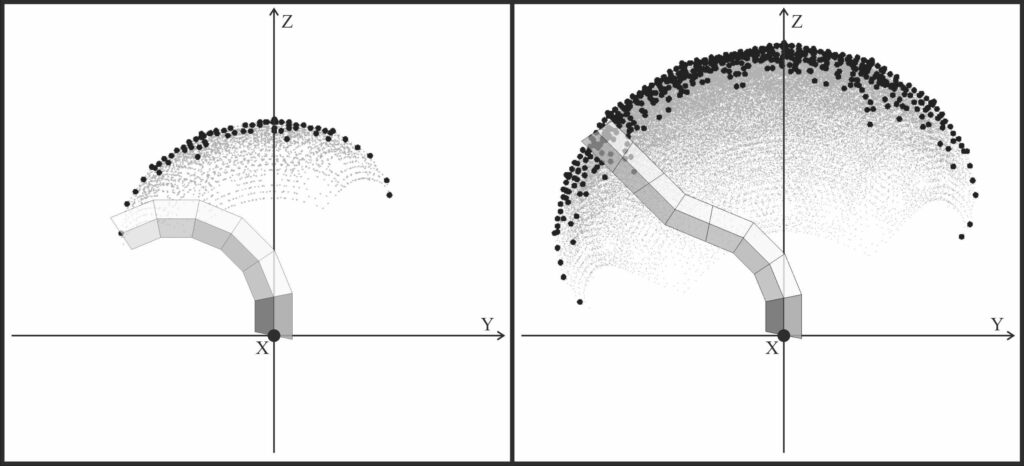

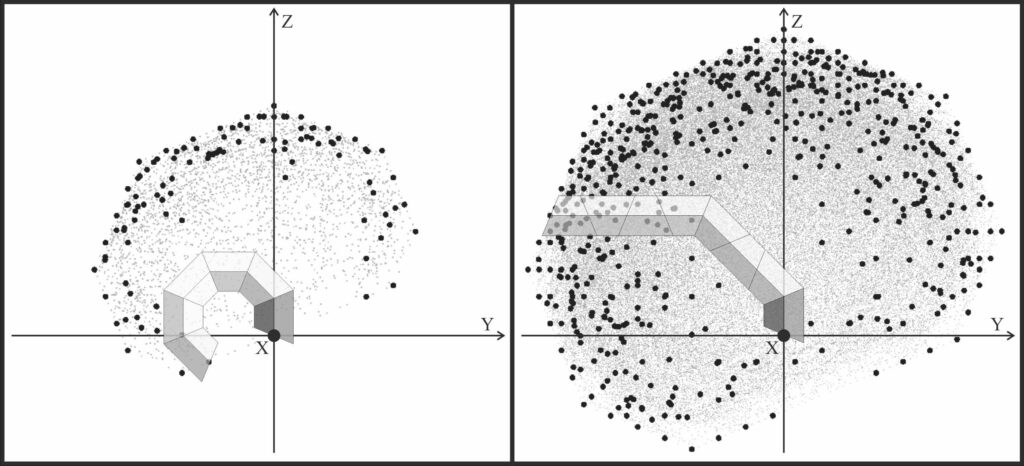

The operational space of a discrete Arm-Z (based on polygonal modules and their dihedral relative twists) forms a point-cloud. Figs. 7 and 8 illustrate four examples of an Arm-Z manipulator composed of hexagonal modules with six discrete relative twists and their respective operational spaces. The sizes and „thicknesses” of these point-clouds grow with the number of modules. Moreover, the geometrical parameters of each module influence the properties of the operational space. In some scenarios the task for the manipulator can be localized but high precision would be required (Fig.7). In other scenarios the task can be less localized at the expense of the tip precision (Fig.8).

For continuous Arm-Z the operational space forms a complex 3D surface which has voids. This means that in general, the tip of Arm-Z can not reach all points in 3D space within its range, but can reach specific points with certain accuracy (error). Moreover, Arm-Z, does not have to be fixed at the base (so it can become a locomotor), and the number of modules can be altered (i.e. its length is adjustable). Nevertheless, the main focus in this proposal is the Arm-Z as a robotic manipulator.

The research questions

The preliminary research on Arm-Z has shown that it is a feasible concept and the virtual model of Arm-Z successfully performs certain tasks [4]. However, it is not clear how precise and controllable Arm-Z can be. These are the research questions of this project:

- What is the most suitable mathematical description of Arm-Z?

- What are the optimal parameters of the Arm-Z modules for given criteria?

- What is the operational range of Arm-Z and how efficiently can it fill the 3D space around it?

- What is the expected accuracy of control of Arm-Z when considering discrete nature of rotations (as it is the case for step motors)?

- What are the optimality criteria for controlling Arm-Z?

- Maximization of the simplicity of the control?

- Minimization of wobbling of the entire Arm-Z?

- Maximization of the „smoothness” of translation of the tip of manipulator?

- Which control methods are suitable for Arm-Z (PID-based control, reinforced-learning, meta-heuristic)?

- What are the physical and mechanical limits regarding stability and strength of the „chain” of Arm-Z modules and how are they related to the local internal structure of the base module?

- What are the requirements for Arm-Z module joints in order to bear expected loads? Such joints must also support quick and simple release and assembly.

- How does the system cope with vibration, stress and deformation?

- How to quantify these and, perhaps, other criteria in order to produce the most versatile design?

- After identification of the limitations of Arm-Z, what are the potential applications, especially in responsive (kinetic) architecture?

Significance of the project

State of the art

This project merges the concept of extreme modularization with trunk/snake-like robotic manipulators.

The snake mechanism is a redundant system which, however, makes snakes supremely adapted for various habitats. Analogously, in irregular environments, bio-inspired trunk-like robots in some cases perform better than more conventional wheeled, tracked and legged forms of robotic mobility. Research on snake robots has been conducted for several decades. Snake locomotion has been studied empirically already in 1940s [5]. 50 years later, the first mathematical model has been developed and trunk-like locomotors and manipulators have been proposed in [6]. Trunk-like manipulators have very specific movement characteristics which makes them especially useful in situations where classic robotic arms cannot be used. Such manipulators can transport working heads in very complex, narrow, confined, cluttered spaces which are inaccessible by any other means. Reaching range can be of order of tens of meters and actions can be accomplished in hazardous environments. They can perform tasks like welding, cleaning, visual inspection and any other which can be realized by the head mounted on the manipulator tips. It should be stressed that the existing solutions in this field are very limited. Only a few companies offer such type of manipulators, and these are rather experimental (Fig.9). The topic is still actively researched so the results of this project will have impact on the field in the future.

Additionally, trunk/snake-like manipulators may have relatively large number of degrees of freedom (DOF) (however, there are exceptions). This contrasts with the classic robotic arms with low number of DOFs which are widely used in the industry. In the case of Arm-Z, the number of DOF is equal to the total number of the connected modules. Besides the possibility of performing complex actions, large number of DOF introduces the possibility of high fault tolerance and robustness. It aligns well with the concept of hyper-redundant manipulators (HRM, [7]). Their advantages come at a price of notoriously difficult control due to their highly non-linear nature.

For example, the inverse kinematics problem for a typical industrial robotic arm can be solved relatively easily (e.g. [8]) and therefore the control of such arms is straightforward. On the other hand, the control of a bionic trunk requires sophisticated artificial intelligence methods [9,10,11]. However, in return, one can profit from all the important advantages of trunk-like HRMs. For further details on this interesting class of robotic manipulators see [12].

The concept of extreme modularization is relatively new, and less explored. In general, research on structural optimization of modular structures seems to be relatively sparse. Ref. [13] considers layout optimization of a modular bridge, where the design variables are effectively discrete and encode the choice from a predefined set of local module topologies. Simultaneous optimization of a family of a few vehicle structures at the level of the shared basic beam components is discussed in [14].

Truss-Z was the first Extremely Modular System, introduced in 2011. It is a modular skeletal system for creating free-form ramps and ramp networks among any number of terminals in space. The research on that system is relevant to all Extremely Modular Systems. It focused on discrete topological and geometric optimization of the base module [15]. Evolutionary algorithms have been successfully applied for optimization of single- and multi-branch layouts, and the results have been presented in: [16] and [17], respectively.

Exhaustive method – graph-theoretic depth-first search algorithm has been successfully applied for finding the ideal Truss-Z single-branch layout in a highly constrained environment [18]. The primary analysis of deployable module has been presented in [19].

The issues of structural design of TZ module including topological optimization of the placement of diagonals, the sizing of members’ cross-sections, the selection of materials, assembly method, etc. have been addressed in: [20, 21, 22].

Particularly relevant to the proposed project, was the problem of optimization of Truss-Z where the number of modules was given beforehand and the objective was to place it in a given topography minimizing the earthworks and existing trees removal under self-collision prohibition. This problem has been recently tackled by the applicant in [23]. Good solutions have been achieved by implementation of image processing (IP) and genetic algorithm (GA) subjected to heavy parallelization in a GPU. In that paper, the self-collisions and other object violations (with ground \& trees) have been assigned different weights.

Justification for tackling specific scientific problems

The problems of optimization and reconfiguration control of modular pipe-like structural systems are meaningful scientific problems for the following reasons:

- Arm-Z represent a large class of reconfigurable structures.

- The concept of Arm-Z is based on modularity and its initial mathematical model can be done efficiently.

- The synergy among modules (which in principle are relatively simple) results in complex, emergent and planned actions which is interesting and meaningful.

- Responsiveness – i.e. reconfiguration and shape control are major challenges in architectural and engineering design.

- An extreme example of global shape control of a pipe-like structure is a robotic trunk-like manipulator. Controlling such manipulators is a well-established and difficult challenge in robotics. Our approach is novel and comparison with the findings in this field would be valuable.

- The problem of consistent representation of several structures at the local level of a single shared substructure is not well recognized yet in the field of mechanics. However, it would substantially simplify global optimization of multi-unit modular structures.

Justification for the pioneering nature of the project

In the proposed project basic research is challenging, interdisciplinary, and the approach is unique:

- It introduces a concept which is relatively simple mechanically in comparison to classic solutions.

- It studies a novel way of motion control where complex movement is achieved by synergy of very simple movements (solely by the relative twists of the modules).

- The extreme modularization brings the potential of inexpensive mass production.

- Arm-Z has ability of changing its length.

- It introduces a topology optimization framework for modular structures in which the optimization is performed locally at the level of a single module with the rest of the structure represented by the interface loads.

- It introduces circular modules (instead of polygonal) which implicates continuous motion (instead of discrete).

- It introduces the problem of robustness to Extremely Modular Systems in general and Arm-Z in particular.

- A part of the project is devoted to local structural optimization of the modules. There is a limited amount of related research on topology optimization of periodic structures, see, e.g., [24, 25]. Even though periodic structures with various types of periodicity are considered (translational, rotational, etc.), the periodicity is always well-defined and so is the global configuration of the entire structure. Similarly, the number of modules and the global geometry of the modular structures considered in [26, 27] is also well-defined. Here, we will consider modular structures which can be composed of a variable and unknown in advance number of units connected in various and unknown in advance configurations (relative twists). This means that instead of a single global periodic structure we need to consider a large number of very different structures, each composed of the same congruent units but connected in various manners and in various numbers. The number of such global structures grows exponentially with the number of involved units, which renders the approaches used in theretofore research computationally unfeasible. We will offer a novel solution based on representing the global optimization problem in terms of a local optimization problem of a single unit subjected to multiple local loads.

- It introduces intensive parallelization in order to achieve efficient real-time control of a complex highly non-linear system by means of GPU.

Impact of the project results on the research field & scientific discipline

Arm-Z belongs to the family of Extremely Modular Systems and represents a novel design philosophy. The first EMS developed by the applicant was Truss-Z introduced in 2011 [15]. Since then a number of new Extremely Modular Systems have been introduced and the concept is gradually and steadily gaining attention in the research community in various disciplines: architecture, civil and space engineering, structural mechanics and computer science. Accordingly, the proposed project is also multidisciplinary and contributes to the research in the following fields:

- Control theory of hyper-redundant manipulators

- This field of research still remains rather unexplored. Due to specific, modular nature of the problem, classic control approaches are not efficient and researchers look for alternatives: artificial intelligence (e.g. neural networks, reinforcement learning) or heuristic methods.

- The results will contribute to the development of new approaches in discrete-continuous control of multibody systems.

- New applications of artificial intelligence and heuristic optimization to control the shape transition

- Since real-time operational regime is desired, novel implementations of massively parallel platforms are planned (e.g. with GPU).

- Application of reinforcement learning for control of Arm-Z.

- Structural mechanics

- Development a framework for consistent hierarchical representation of modular structures that exploits the congruence of units.

- Application of this framework to topological optimization of modular structures at the local level of the congruent unit.

- Theory of design

- Introduction of extremely modular kinetic elements for responsive architectural and engineering design.

- Introduction of agent-based modelling for self-organization of extremely modular systems.

Work plan

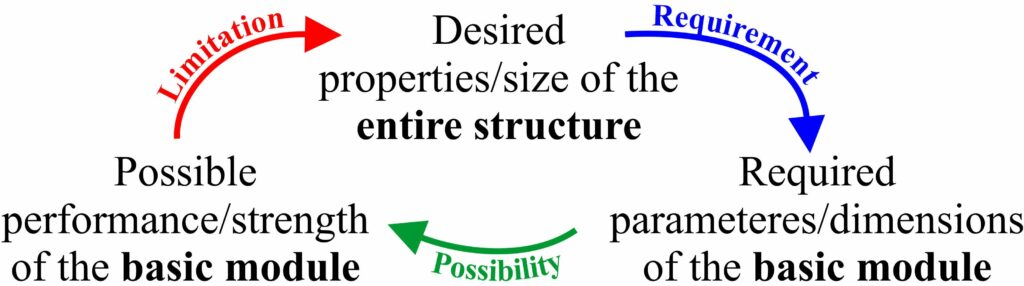

Since the project is multidisciplinary, it naturally divides in work-packages to be completed by specialist sub-teams. The process of determination of design parameters for Arm-Z is iterative as illustrated in Fig.10.

WP1: Control algorithms of hyper-redundant trunk-like modular manipulator

Among other fields, the concept of Arm-Z relates to the field of robotics:

- The main focus of this project is the control of Arm-Z as a robotic manipulator (with one end fixed).

- Additionally, control of Arm-Z as a trunk-like locomotor (with both ends free) will be considered.

In this work-package:

- Various control algorithms will be applied and evaluated.

- The most efficient algorithms will be selected.

- Classic control techniques (e.g. PID-controller) will also be considered for the evaluation purposes. However, due to the high non-linearity of the Arm-Z it is expected that heuristic approaches will be probably more effective.

WP2: Structural optimization of Arm-Z module & global mechanical limits

Other work-packages investigate Arm-Z at the level of their geometry, including geometric transitions and control of the global shape. This work package applies and adapts the methods of computational mechanics to analyze and optimize the internal mechanical structure of a unit and the entire Arm-Z construction. In particular, we will heavily exploit the congruency of units and:

- adapt existing methods of model reduction to model an Arm-Z in a hierarchical way, that is (i) at the level of the interface degrees of freedom (DOFs) common to the neighboring units and (ii) at the local level of a single congruent unit;

- develop and adapt the fixed ground structure optimization technique to optimize the local internal structure of a single unit.

Finally, the developed hierarchical model with optimized units will be used in the task of

- assessment of global mechanical limits of the entire Arm-Z.

Model reduction

Arm-Z is composed of a number of congruent units. We will consider model reduction techniques [27], starting from the classical Guyan reduction approach [28], and adapt them in order to develop a hierarchical model of the entire Arm-Z. A two-level model will be investigated:

- The global level will model Arm-Z at the level of the interface DOFs common to the neighboring units. Condensed structural matrices (reduced to the interface DOFs) will be used as substitutes of the units. Possible internal loads of the units will be reduced to the interface DOFs as well.

- The local level will model a single congruent unit by means of the finite element (FE) method. We will consider a number of possible FE models and select a model suitable to perform local structural optimization, which is the next task within this work package. The (optimized) local model will be used to compute the substitute structural matrices used at the global level.

Local optimization

The number of possible geometrical configurations of Arm-Z grows exponentially with the number of units it is composed of. This fact renders global structural optimization of Arm-Z computationally unfeasible. Moreover, since the Arm-Z units are congruent, any attempt at global optimization will result in heavily redundant computations. We will exploit congruency and use the hierarchical model developed in the previous task. This will allow us to focus on local structural optimization of a single unit instead of the global structure. In particular, we will:

- represent the multiple global configurations of the Arm-Z at the local unit level in terms of a local multi-load case, and

- adapt the ground structure method [29] to the multi-load case and use a relatively dense ground structure to perform local structural optimization of the unit.

An example ground structure is shown in Fig.11. As the internal structure and the equivalent loads of a unit are coupled, we will need to consider iterative optimization schemes, as illustrated in Fig.10.

Local optimization

Finally, global mechanical limits of the Arm-Z will be investigated. We will use the developed hierarchical model with the optimized unit to assess the global limits in terms of the criteria such as the maximum number of units (the maximum span), maximum load, maximum acceleration in shape transitions, subject to the constraints as maximum stress and maximum local compressive load.

WP3: Experimental set-up & verification

In this work-package a test set-up will be installed and experimental evaluation of the multi-module hyper-redundant demonstrator will be performed. Experimentation will include control tests, numerical model verification, interpretation of the results, etc. The physical demonstrator will:

- execute physical transformations according to given scenarios;

- naturally and intuitively demonstrate the outcome of the developed algorithms;

- serve as a controller feeding the global state into a computer for further analysis;

- demonstrate the capability of Arm-Z to change the number of modules (its length);

- demonstrate the operability at various shapes/geometric proportions of the base module.

The physical demonstrator

Variety of mock-ups and primary prototypes of the Arm-Z modules will be produced as the project progresses. However, the final version of the modules requiring proficiency in the field of robotics will be outsourced according to our specifications and assembled by our team. The physical demonstrator will not have to be perfect in the sense of WP2, but it is expected be a proof-of-concept showing feasibility of the used control algorithms and versatility of the Arm-Z concept. Figure 12.1 shows a mock-up Arm-Z demonstrator used in our previous research [4]. It has been 3D-printed and the configurations have been set up manually. The diameter of each module is 75 mm.

3. Schematic sequence of Stewart platforms emulating Arm-Z of adjustable module size.

The concept of Arm-Z is highly scalable, both in size and functionality. The mechanism of Arm-Z demonstrator will be based on computer-controlled servo drives. The kinetic system of Arm-Z mechanism will be scalable in such a way that at the beginning of the kinematic chain the servos with be supplied with greater power which will be reduced towards the tip of Arm-Z. Nevertheless, the geometry of Arm-Z modular elements will be constant throughout the entire length of the mechanism. Thus, it will be possible to simultaneously examine the behavior of the Arm-Z mechanism and optimize the power supply for its movement. In the planned demonstrator, each module will have an independent control unit and rechargeable energy supply and the communication with the units will be wireless. Each module will consist of the following essential parts:

- a 3D-printed shell with metal or advanced plastics (or composite); the exact shape will be designed in the course of the project,

- a servo mechanism allowing the relative rotation,

- solutions minimizing the necessity for mechanical gears,

- a minicomputer controlling the servo and communicating with the main CPU unit or with the other modules; usage of Onion Omega 2 WiFi is planned for this task,

- a rechargeable battery capable of powering the servo and controller for a reasonable time; each module will have a USB connection allowing for charging,

- a dedicated quick connector making it possible to easily lock/release modules together with appropriate mechanism allowing for easy rotation.

Presently, the total costs necessary to prototype a single module may be relatively low, and the cost of the final product is expected to be very competitive. The use of WiFi for each module substantially simplifies the assembly and operation e.g. by avoiding cabling as much as possible so it will not interfere with the movements, etc. It also aligns with the concept of the Internet-of-Things (IoT).

The construction of the demonstrator module

In principle, each Arm-Z module is a rigid shell body connected in a sequence by joints allowing for relative twists only (1 DOF). However, in order to demonstrate scalability of the system, Arm-Z module based on Stewart platforms is also considered. This would allow to control the shape and size of each individual module, as shown in Fig.12.2. In such case, the shape of each individual module could be easily pre-set and Arm-Z would become a sequence of fixed Stewart platforms still controlled by relative twists (Fig.12.3). Such fixed Stewart platform becomes a relatively lightweight and rigid skeletal structure. The module shape could be adjusted to a certain degree, and such skeletal demonstrator is expected to be relatively inexpensive to make and having required functionality for testing and evaluation.

It is also imaginable to use directly Stewart platforms as modules for a hyper-redundant manipulator. However, even a single Stewart platform, which has six degrees of freedom (6 DOF), is a technological challenge not to mention their multiplied sequence. Most importantly, such a concept is on the contrary to the philosophy of this project which focuses on fundamentally simpler approach.

WP4: Identification of challenges in architecture & engineering for Arm-Z

The preliminary study suggests that Arm-Z could serve as load-bearing kinetic structures capable of shape-changing. However, the required strength, precision and range of movements greatly vary among potential applications. The exact focus of this work-package depends on the results from WP1 and also WP2 & WP3. The scope of this work-package includes investigations on:

- Self-supporting architectural elements adapting to changing natural conditions, e.g. sun-shades (Fig. 4.3).

- Besides controlling insolation, Arm-Z based architectural adaptive protection can shield from noise, rainfall, wind, sight, etc.

- The ergonomics of reconfigurable habitats require certain ranges of diameters for creating functional and safe inhabitable and auxiliary structures.

- The extreme-environment conditions pose certain thermal/radiation requirements for insulation which will be reflected in the minimal wall thickness of respective module.

- For kinematic modular architectural elements – the ranges of dead and dynamic loads to be determined. This will have to be reflected in the selection of potential materials and ranges of wall thicknesses.

- Investigation of industrial challenges such as tunnel boring, stabilizers, etc.

- The environment (size and degree of flexibility) and task (the weight of the working head) for potential operation will determine the scale of the robotic trunk/snake-like manipulator, etc.

WP5: Case-studies of Arm-Z in architecture & engineering design

The final selection of conceptual case-studies of Arm-Z potential implementations in architecture and engineering depends on the findings of WP4, but also on WP1 & WP2. However, the preliminary research suggests the selection will be made from the following options:

- Self-supporting architectural shield capable of adaptation to changing (natural) conditions such as: insolation, glare, noise, rain, wind etc. (see Fig.4.3).

- Self-actuating architectural manipulator. E.g.: a self-deploying and stowing: street lamp, sun-shade etc. The actuation can be triggered by light, humidity, water, noise, temperature etc.

- Load-bearing responsive (kinetic) columns capable of shape-changing (see Fig.4.2). The response can be based on safety (e.g. to overload) or can be programmed for aesthetic/artistic purposes.

- The head of Tunnel Boring Machine (TBM) mounted to Arm-Z manipulator (Fig.5.2).

- Functional head (e.g.: viewing, maintenance, welding, etc.) head mounted on Arm-Z (Fig.5.1).

Results of the initial research

The problem of robotic manipulators has been studied for decades, and already resulted in a number of high-tech industrial applications [30, 31]. The problem of modular robot control is also an intensively studied [32, 33]. However, the shape transition of a structure composed of congruent modules with 1DOF is our pioneering work [4, 34}. Although manipulators are usually designed to cover continuous space within given range and to perform motion as smooth as possible, in our preliminary research, the Arm-Z modules were based on polygons, which results in non-continuous (step) motion. In that stage of our research it has been decided for the discrete nature of the Arm-Z system for the following reasons:

- Arm-Z configurations are described as sequences of dihedral rotations and expressed by lists of integers.

- It was relatively easy to fabricate an inexpensive mock-up model of Arm-Z which can firmly hold its shape in any configuration without any energy supply (Fig.12.1).

- Step-motors have been considered to power the relative twists of Arm-Z modules. They also support step-motion, which, however, has much higher resolution.

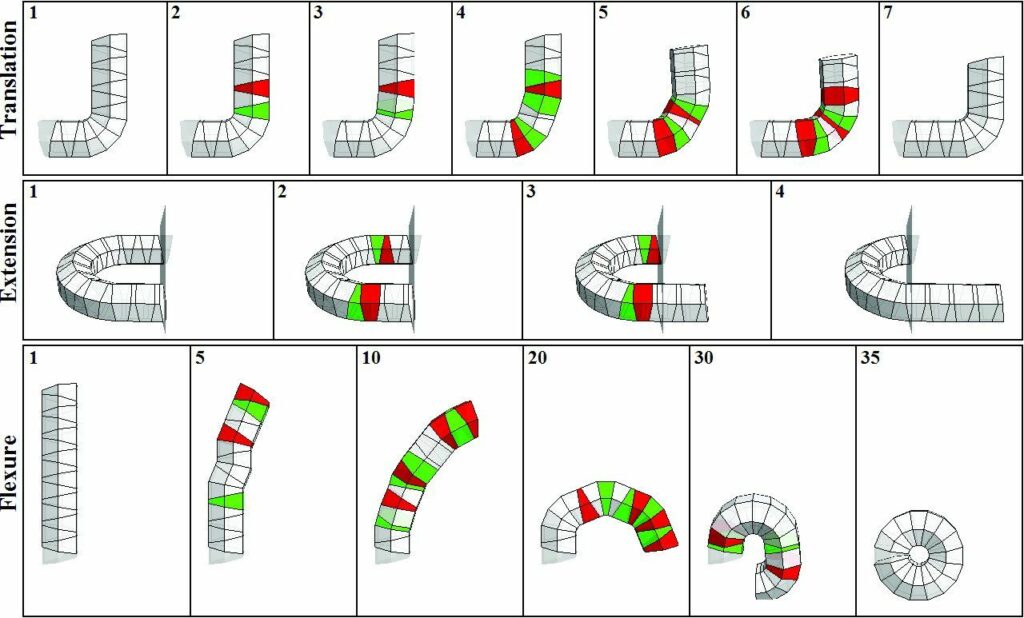

- Modules made of flat rigid panels can be folded efficiently for transportation as demonstrated in [3].

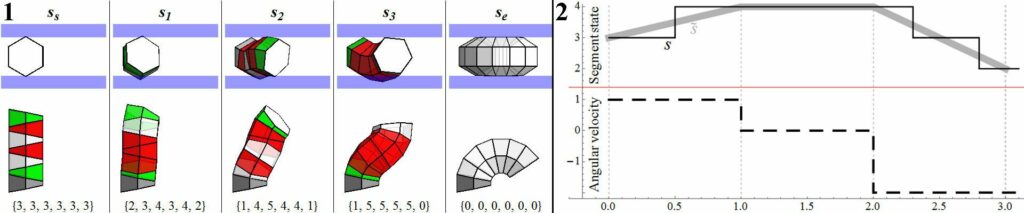

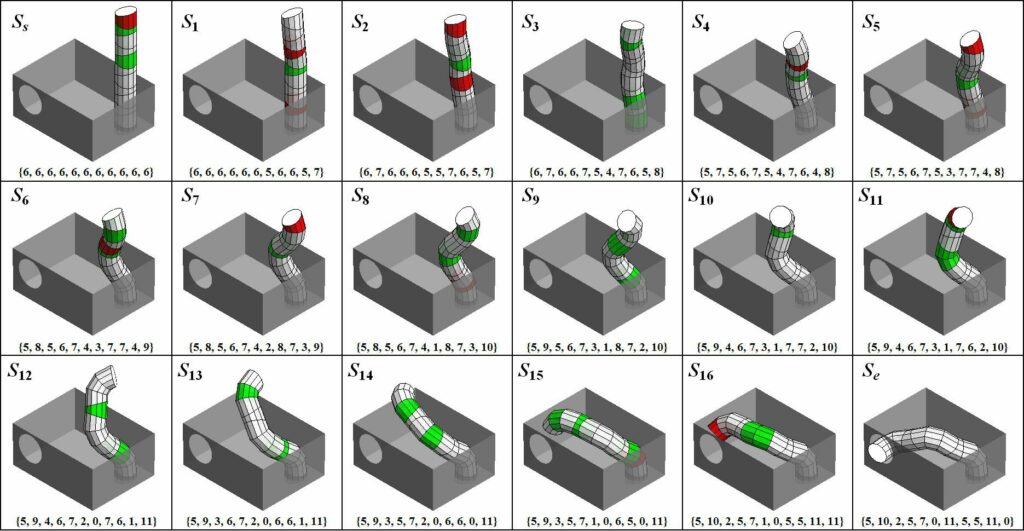

The initial work [2] showed that Arm-Z can perform three fundamental actions: flexure, translation and extension, as illustrated in Fig.13. For Arm-Z based on a polygon of n sides (n-gon), the number of relative twists for each module is equal to k. Fig.6 shows two examples: dodecagonal and hexagonal. A „straight pipe” for: square, hexagonal Arm-Z will be encoded as a sequence of integers: [2,2,…], [3,3,…], respectively. For Arm-Z of any base, a sequence of 0s will form an arc up to a full torus (see Fig.2.2). The problem of Arm-Z transition has been formulated in our first paper on Arm-Z [34] as follows:

- There are two given configurations (states): Start (Ss) and End (Se).

- The transition environment is constrained by a narrow slot.

- Find the transition between Ss and Se.

- The number of transformation steps is given: 4.

- In one step, each module of a n-gon base Arm-Z can rotate by at most 2π/n dihedral angle. E.g. each hexagon-based module at one time-step can rotate by at most π/3, that is by: {π/3, –π/3, 0}.

- The summarized wobbling perpendicular to the „bending plane”, i.e. in the y-direction to be minimal.

Fig.14.1 illustrates this problem and shows the ideal solution. It has been found by exhaustive search, which can only work for very few modules in sequence. The growth of the number of all possible Arm-Z transition sequences is double exponential. Here the number of potential solutions is already 262,144.

The main difficulty of Arm-Z transition is that this problem is highly non-linear and difficult to trace. This means that small changes in a small number of segments can lead to different overall shapes. For these reasons gradient-based methods are unfeasible. Thus it is rational to apply a heuristic method which can quickly sample as large part of the parameter space as possible. In [4] we implemented Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) which does not guarantee that the optimum is found, however, a very large space can be searched and there are no requirements regarding the objective function. The motion of all modules was parametrized by angular velocities, and a vector of these velocities formed a single particle in PSO, which can be evaluated by objective function of an arbitrary form. Moreover, since the computing threads are independent, the calculations were massively parallelized with GPU. As a result, for realistic problems acceptable solutions were found in a matter of minutes/hours, depending on their complexity. The state of each module can be represented by an integer $\si$, $\si \in [0,\dots,n-1], \si \in \mathbb{I}$. However, for the purpose of encoding solution for reconfiguration, a corresponding continuous counterpart $\sr$ was introduced, $\sr \in \mathbb{R}$. The discrete value representing the real integer state is the nearest-integer, $\si = \nint{\sr}$ (here $\nint{}$ denote the nearest-integer operator, e.g., $\nint{4.6}=5, \nint{2.5}=2$) In order to allow for a dynamical change, with each element i, there is associated an angular velocity $\omega_i(t)$ which can be time-dependent (thus acceleration and deceleration are possible). The time runs from ts to te which correspond to the initial and end states, respectively. Thus the discrete states of the i-th element during the transition are given as:

$\si_i(t) = \nint{\sr(t)} = \nint*{ \int_{t_0}^t \omega_i(t) {\rm dt} + s^s_i }$, where $s^s_i$ is the initial state at time $t_s$.

Consequently, the global transition is controlled by the velocity functions

$\omega_i(t)$. It was assumed that the transition time is divided into $\ninter$ equal parts (number of intervals”), δ t = (t_e-t_s)/\ninter$ during which the velocity is kept constant, $\ninter$ being a parameter. Thus the resulting real-valued function $\si_i(t)$ is piecewise linear, and $\omega_i$ is simply defined by a real valued vector with $\ninter$ elements. For the given $\ninter$ (which is the same for all the segments), the transition for the entire system was defined by a matrix Ω of $\ninter \times l$ real values for the given time span te – ts. Note that the assumption that the $\ninter$ parts are equal is arbitrary. In principle the transition time could be divided into parts of any length. However, this would introduce additional variables into the optimization process making it more difficult due to the curse of dimensionality”. Figure 14.2 shows a sample transition for a single module with initial position 3 and the particle vector ωi = [1,0,-2].

Similar approach is planned as a starting point for continuous Arm-Z. Besides PSO, a classic genetic algorithm will be employed. Novel encodings will be implemented with varied number of intervals and their lengths. As an alternative, parametrized polynomials will be considered as functions encoding module positions. The polynomial coefficients will form particles (PSO) or individuals (in genetic algorithm) which are subject to optimization. In order to allow for real-time optimization efficient

implementation and massive parallelization of the algorithms will be necessary.

The transition should minimize the sum of the buckling error in a slot, so the objective function to be minimized is $f=\sum_{i=1,…,n} | \delta_y(i)+D$, where $\delta_y(i)$ denotes the absolute difference between the y-coordinate of the centroid of the initial module and the $i-$th module, $\delta_y$ measures deviation from the y-plane (Fig.16). In the same paper [4] we also proposed a significantly more complex (and realistic) problem:

- There is a given initial state of Arm-Z in given environment.

- Find the transition of Arm-Z to the final (unknown beforehand) configuration so the tip of the Arm-Z reaches as close as possible to the given point.

Fig.16 shows the best solution found by PSO. This problem is closely related to the robotic arm control.

In the examples shown above the problem of collisions with the environment have been considered, however, due to the length (shortness) of the manipulator, the problem of self-collisions did not occur. In realistic applications, however, this problem must be considered.

Risk analysis

The risk of failure of any task in the proposed research can be assessed as slim. The manually-operational mock-up prototype of Arm-Z has already been built, as shown in Fig.12.1. In principle, the creation of a fully functional Arm-Z demonstrator is a relatively straightforward technological task.

Regarding algorithmic and software engineering for Arm-Z control, we will develop and modify already functional code, which has produced meaningful results in the reduced problems documented in: [34, 4, 23].

Practically, the only major concern in the Arm-Z control is the speed of our algorithms generating optimal or near-optimal solutions. It is possible that even with GPU a near-optimal solution could not be found in real-time. In such a case, either:

- An off-line planning path which gives more time for optimization, will be considered.

- The on-line control quality will be evaluated against optimal solutions by limiting the time.

- The entire motion will be combined from pre-calculated partial movements. This will quickly give a sequence of partial solutions of probably acceptable quality.

The structural optimization will deal with a single module subjected to a large number of boundary loads. Even though the module is relatively simple, such an approach may involve a large number of optimization variables and result in unacceptably long optimization times. In such a case, we will consider a Monte Carlo type representative re-sampling of the loads to decrease the computational burden.

Research Methodology

Underlying scientific methodology

Structural mechanics – the important research tasks are related to:

- developing a method to represent a range of global configurations of a modular structure in terms of local, unit-level loads, and

- adapting a technique of structural optimization to the resulting local-level, multi-load problem.

We will review techniques of model reduction [27], including the classical approach of Guyan reduction [28], and adapt them in order to develop a two-level hierarchical model of the entire Arm-Z. The global, master level will be defined in terms of the degrees of freedom (DOFs) that belong to the interfaces between the neighboring units. The local level will reduce the global interface interactions to the local loads of the units. As all the units are congruent, we will derive this way a local multi-load representation of the global configuration. For structural optimization, we will adapt the ground structure approach [29] and apply it to the local, multi-load optimization problem. Coupling between internal structure and equivalent loads will be addressed with iterative/optimization schemes.

Global shape reconfiguration – a number of algorithms will be considered. They will be based on the existing gradient-based optimization; nature-inspired meta-heuristics: mainly genetic algorithms, particle swarm optimization or simulated annealing; reinforcement learning, neural networks and other artificial intelligence methods (this has already been proved to be efficient solution for controlling trunk-like manipulators [9,10,11]). The focus is twofold: on efficient representation (coding) of a candidate solution and tuning of the mentioned well-known algorithms. In order to evaluate efficiency of each considered approach, a number of test scenarios is planned. They will include transformations typical for a robotic manipulator or other interesting cases:

- move the tip from point A to point B

- transport the tip in a confined, narrow space (a task dedicated for a trunk-like manipulator)

- as in 2 with dynamically moving obstacles which are to be avoided

- as in 1 including specific optimization goal (minimization of wobbling, etc.)

- self-displacement by the entire Arm-Z (as a locomotor).

All considered algorithms will be tested in numerical simulations phase in order to find the best solution by means of certain quality measure. In order to perform all tests in reasonable time, efficient implementation on parallel architecture of all approaches regarding coding and optimization methods will be implemented.

An important aspect of research in the framework of the project is study of failure tolerance of the system. In simulations this will be done by assuming failure (lack of response, wrong response) of one or more modules and its influence of the overall performance. By performing statistically meaningful number of calculations, it will be possible to come up to conclusions regarding system resistance to failures which is a fundamental aspect of any hyper-redundant system.

Apart from the simulations, it is expected that working with the demonstrator will give further insight to the problem. Physical device will undoubtedly introduce specific problems which are hard to predict in simulations, which are idealized by nature. For example, it is likely that the objective function of the optimized problem will be modified accordingly, so as to assure proper treatment of mechanical constraints not known at the initial stage of the project.

Techniques and research tools

The details regarding specific implementation of real-time control based on GPU will depend on the control algorithms chosen for this task. Previous research [4] suggests that applying meta-heuristic methods like Particle Swarm Optimization or Genetic Algorithms will be of particular use in order to tackle the highly non-linear control problem. Such meta-heuristics are often quite straightforward to parallelize, including massive parallelization [35, 36]. We are planning to use our dedicated CUDA programs, supported by external libraries [37]}. Generally, in this type of problems GPU is used to efficiently evaluate a large number of individuals in order to speed up the population evaluation. Afterwards, other operators (selection, crossover) can be applied.

Equipment and devices to be used in research

Regarding development, implementation and testing (including study of scaling and efficiency) of the control algorithms for Arm-Z shape transformation, the necessary equipment is available at the host institution:

- Fast desktop machines with GPU;

- A cluster with 256 8-CPU nodes and 32 GPU nodes;

- Department of Intelligent Technologies is equipped with rapid prototyping devices (3D printers, laser plotter, etc.);

- Host institution also provides access to advanced rapid prototyping 3D printer: EOSINT M 280, which allows for fabrication from metals (aluminum, titanium, steels 316L and MS1);

- Laboratory of the Division of Safety Engineering is perfectly suited for the experimental setup.

Project literature

[1] M. Zawidzki. Discrete Optimization in Architecture: Extremely Modular Systems. Springer, 2017.

[2] M. Zawidzki et al.,. Arm-Z: a modular virtual manipulative. In H-P. Schroecker, editor,Proceedings of the 16th Int. Conf. on Geometry and Graphics, pages 75–80, 2014.

[3] M. Zawidzki. Deployable Pipe-Z.Acta Astronautica, 127:20–30, 2016.

[4] M. Zawidzki and J. Szklarski. Transformations of Arm-Z modular manipulator with Particle Swarm Optimization. ADV ENG SOFTW., 126:147–160, 2018.

[5] James Gray. The mechanism of locomotion in snakes. J. Exp Biol., 23(2):101–120, 1946.

[6] S Hirose.Biologically Inspired Robots: Snake-Like Loco-motors and Manipulators. Oxford University Press, 1993.

[7] K. Ning and F. W ̈org ̈otter. A novel concept for building a hyper-redundant chain robot. IEEE Transactions on Robotics, 25(6):1237–1248, Dec 2009.

[8] Richard M Murray, Zexiang Li, S Shankar Sastry, and S Shankara Sastry. A mathematical introduction to robotic manipulation. CRC press, 1994.

[9] M. Rolf and J. J. Steil. Efficient exploratory learning of in-verse kinematics on a bionic elephant trunk.IEEE Trans-actions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, 25(6):1147–1160, 2014.

[10] A. Melingui et al. Qualitative approach for forward kinematic modeling of a compact bionic handling assistant trunk. IFAC Proc. Volumes, 47(3):9353 – 9358, 2014.

[11] V. Falkenhahn, A. Hildebrandt, R. Neumann, andO. Sawodny. Dynamic control of the bionic handling assistant.IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics, 22(1):6–17, 2017.

[12] Gregory S Chirikjian and Joel W Burdick. A hyper-redundant manipulator. IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine, 1(4):22–29, 1994.

[13] A. Tugilimana et al. Conceptual design of modular bridges including layout optimization and component reusability. J BRIDGE ENG, 22(11), 2017.

[14] Bo Torstenfelt and Anders Klarbring. Structural optimization of modular product families with application to car space frame structures.STRUCT MULTIDISCIP O,32(2):133–140, 2006.

[15] M. Zawidzki and K. Nishinari. Modular Truss-Z system for self-supporting skeletal free-form pedestrian networks. ADV ENG SOFTW., 47(1):147–159, 2012.

[16] M. Zawidzki and K. Nishinari. Application of evolution-ary algorithms for optimum layout of Truss-Z linkage in an environment with obstacles. ADV ENG SOFTW., 65:43–59, 2013.

[17] M. Zawidzki. Optimization of multi-branch Truss-Z based on evolution strategy. ADV ENG SOFTW., 100:113–125,2016.

[18] M. Zawidzki. Retrofitting of pedestrian overpass by Truss-Z modular systems using graph-theory approach.ADVENG SOFTW., 81:41–49, 2015

[19] M. Zawidzki and T. Nagakura. Foldable Truss-Z module.Proceedings for ICGG, pages 4–8, 2014.

[20] M. Zawidzki and L Jankowski. Multicriterial Optimiza-tion of Geometrical and Structural Properties of the Basic Module of a Single-Branch Truss-Z Structure. In WCSMO2017, pages 163–174. Springer, 2017.

[21] M. Zawidzki and L. Jankowski. Optimization of modular Truss-Z by minimum-mass design under equivalent stress constraint. Smart Structures & Systems, 21(3).

[22] M. Zawidzki and L. Jankowski. Multiobjective optimiza-tion of modular structures: weight versus geometric ver-satility in a Truss-Z system. Computer-Aided Civil andInfrastructure Engineering, 2019.

[23] M. Zawidzki and J.Szklarski. Effective Multi-objectiveDiscrete Optimization of Truss-Z Layouts Using a GPU. Applied Soft Computing, 2018. ISSN 1568-4946.

[24] Xiaodong Huang and YM Xie. Optimal design of peri-odic structures using evolutionary topology optimization. Struct. and Multidisc. Optimization, 36(6):597–606, 2008.

[25] Z. Zuo.Topology optimization of periodic structures. PhD thesis, PhD thesis, RMIT University, Australia, 2009.

[26] A. Tugilimana et al. Spatial orientation and topology optimization of modular trusses. Struct. Multidiscip. Optimization, 55(2):459–476, 2017.

[27] M. Beitelschmidt P. Koutsovasilis. Comparison of modelreduction techniques for large mechanical systems. Multi-body System Dynamics, 20(2):111–128, 2008.

[28] R.J. Guyan. Reduction of stiffness and mass matrices. AIAA Journal, 3(2):380, 1965.

[29] T. Sokol. A 99 line code for discretized Michell truss optimization written in Mathematica. Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization, 43(2):181–190, 2011.

[30] Joseph F Engelberger. Robotics in practice: managementand applications of industrial robots. Springer Science & Business Media, 2012.

[31] Bruno Siciliano and Oussama Khatib. Springer handbookof robotics. Springer, 2016.

[32] V.Vonasek et al. High-level motion planning for CPG-driven modular robots. Robotics and Autonomous Systems, 68:116 – 128, 2015.

[33] M. Yim, Ying Zhang, and D. Duff. Modular robots. IEEE Spectrum, 39(2):30–34, 2002.

[34] M. Zawidzki and J. Szklarski.Preliminary optimization of Pipe-Z reconfiguration. In G. Varady P. Ivanyi, B.H.V. Topping, editor,Proceedings for PARENG 2017, pages 1–12, 2017.

[35] Yue-Jiao Gong et al. Distributed evolutionary algorithmsand their models: A survey of the state-of-the-art. ApplSoft Comput., 34:286 – 300, 2015. ISSN 1568-4946.

[36] P. Pospichal et al. Parallel genetic algorithm on theCUDA architecture. In European conference on the applications of evolutionary computation, pages 442–451, 2010.

[37] F.A. Fortin et al. DEAP: Evolutionary Algorithms MadeEasy. J. Mach. Learn. Res., 13(1):2171–2175, 2012.